On first encounter with Hilma Af Klint (1862-1944), one is forced to revise all perspective on the tumblr-ready faux mystic visual cesspool into which millennials cheerfully dump their soothing salts and around which they place their essential oil-suffused tea lights and crystal shards.

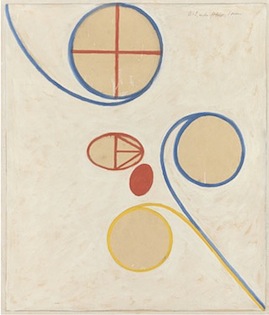

This woman’s postmortem presence continues to defy explanation. Evidence suggests that she (not Kandinsky or Mondrian) holds the distinction of being the very first Western abstract artist. She was experimenting with automatic drawing long before any such thing was conceived in the art world; her paintings abuzz with the gravity and wonder of first-hand contact with invisible forces.

Not much is known about either af Klint’s personal or professional life. What shreds any attempt at analysis is the fact that she kept her serious works carefully hidden; backed by a decree that none of it be shown until at least 20 years after her death. The only paintings she allowed to reach the public during her lifetime were the innocuous classical landscapes and portraits by which she made her earthly living. While Kandinsky was traipsing about Europe repeating his claim ad nauseum to the title of “First Abstract Painter”, much of af Klint’s catalog had existed in hiding for years. Her unexpressed reasons for sequestering her most vital works are the stuff of dreams.

Working as part of an all-female group known only as ‘The Five’ (de fem in Swedish, layers of meaning), she spent most of her time exploring emerging Theosophical ideas and attempting to establish communication with higher personal and impersonal beings. Throughout her secret career, she completed certain works as a “channel” of her spiritual guides, while others turned her own interpretive lens on her points of contact with the unseen. She played heavily upon the visible vs. invisible forms of things, and the confluence of internal and external powers she came to know in her cartography of the other side.

“All the knowledge that is not of the senses, not of the intellect, not of the heart but is the property that exclusively belongs to the deepest aspect of your being…the knowledge of your spirit.”

There’s a whole lot we’ll never know about why this woman was compelled to make over a thousand classified paintings. The details of her glowing orbs, feathery, fallopian organisms and towering superstructures are lost to us for the time being. But the care in labeling, compilation of color systems, diagrammatic symbolism all point to a very intentional mode of expression. Most of all, these images have a life of their own, a beauty that supersedes any type of dialectical understanding.

In an era of contentless self promotion and cut-and-paste hubris, Hilma af Klint is psychic triage and the assurance that Mystery isn’t dead.